Week 9

European Immigrants

in America

SOCI 231

Lecture I: October 28th

A Quick Reminder

Response Memo Deadline

Your sixth response memo—which has to be between 250-400 words and posted on our Moodle Discussion Board—is due by 8:00 PM today.

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

Midterm Paper Deadline(s)

If you have yet to submit your midterm paper, it is due by —

- 8:00 PM on Friday, November 1st

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

To submit the paper, visit the following page on Moodle.

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

Please submit the paper as a .docx or .doc file.

\(\LaTeX\) User?

Check outpandoc.

A Quick Reminder

An Election Is Looming Over the Horizon

Flux and Choice in American Ethnicity — Mary Waters

Ethnic Options

Census and survey data on later-generation white ethnics in the 1970s and 1980s have yielded an interesting and what may appear at first to be a startling finding—ethnic identity is a social process that is in flux for some proportion of the population. Far from being an automatic labeling of a primordial characteristic, ethnic identification is, in fact, a dynamic and complex social phenomenon.

(Waters 1990, 16, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Ethnic Options

Most people assume that ethnic groups are stable categories and that one is a member of a particular ethnic group because one’s ancestors were members of that group. Thus one is French because one’s ancestors were French and because the category French exists and has meaning. One may know that the Normans, the Franks, the Burgundians, and the Gauls were once separate groups who came to be known as French, but that does not necessarily make the category French any less “real” to a particular individual.

(Waters 1990, 17, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Ethnic Options

How do sociologists conceptualize ethnicity?

Ethnic Options

[M]ost sociologists study ethnicity from social, situational, or rational points of view, seeking to understand the forces in society that create, shape, and sustain ethnic identity. They often defend such approaches from an opposite, biologically based understanding of ethnicity … Sociologists’ definitions of ethnicity stress that it involves the belief on the part of people that they are descended from a common ancestor and that they are part of a larger grouping.

(Waters 1990, 17, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Ethnic Options

Sociologists have shifted focus to the construction, destruction and reconstruction of ethnic boundaries.

Ethnic Options

Back to Week 7

Ethnic Options

Back to Week 7

Ethnic Options

Back to Week 7

Ethnic Options

Back to Week 7

Ethnic Options

Back to Week 7

A Question

If boundaries are in flux, are immigrant-origin people free to choose any ethnic “label” or “identity” they desire?Constraints

[P]eople’s belief that racial or ethnic categories are biological, fixed attributes of individuals does have an influence on their ethnic identities. This popular understanding of ethnicity means that people behave as if it were an objective fact even when their own ethnicity is highly symbolic. This belief that ethnicity is biologically based acts as a constraint on the ethnic choices of some Americans, but there is nonetheless a range of latitude available in deciding how to identify oneself and whether to do so in ethnic terms.Whites enjoy a great deal of freedom in these choices; those defined in “racial” terms as non-whites much less.

(Waters 1990, 18, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Constraints

Black Americans, for example, are highly socially constrained to identify as blacks, without other options available to them, even when they believe or know that their forebears included many non-blacks.

(Waters 1990, 18, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Constraints

Du Bois (1897)

Constraints and Options

For white ethnics, however, ethnic identification involves both choice and constraint. Children learn both the basic facts of their family history and origins and the cultural content and practices associated with their ethnicity in their households. This process itself often involves a sifting and simplifying of various options.

(Waters 1990, 19, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Constraints and Options

The interaction between choice and constraint in ethnic identification is most obvious in the case of the children of mixed marriages. But even the relationship between believed ethnic origin and self- identification for people of single ancestry involves a series of choices. For instance, individuals who believe their ancestry to be solidly the same in both parents’ backgrounds can (and often do) choose to suppress that ancestry and self-identify as “American” or try to pass as having an ancestry they would like to have. The option of identifying as ethnic therefore exists for all white Americans, and further choice of which ethnicity to choose is available to some of them.

(Waters 1990, 19, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Discussion I

Ethnic Identification and Assimilation

In small groups, discuss how patterns of (or the social mechanisms underlying) ethnic self-identification are related to the

assimilation of immigrant-origin people.

The Choices Adults Make

Choosing an Ancestry

The ways people come to an ethnic self-identification are highlighted in cases where an individual believes that his or her parents are of different ancestries and must then make a decision about which ancestry to identify with. Sometimes this is not even a decision, but is socialized so early in life that people are not even aware of it … When faced with a heterogeneous group of ancestors, a person who is going to simplify or identify with one or the other side is slightly more likely to choose the father’s ancestry, but obviously it is not an automatic process in which all individuals choose the paternal line to determine ancestry.

(Waters 1990, 21–22, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Choosing an Ancestry

Even though it was a breakthrough for the 1980 census to allow more than one ancestry … (Waters’) interviews suggest that such surveys underestimate the mixing of the population. This is because it is often assumed when analyzing these surveys that only those giving a multiple ancestry are the result of ethnic intermixing. However, people frequently make choices and sift through their ancestries before naming an ancestry. Many people who give a multiple ancestry have simplified from an even greater number of possibilities, and many people who give a single ancestry are actually aware of multiple possible ancestries in their backgrounds.

(Waters 1990, 22, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Choosing an Ancestry

The ways in which people described their family histories and the ways in which they came to their answers reveal just how much sifting and sorting occurs even before they consider the question. The complex interplay among the different aspects of an individual’s ethnic identification was an overriding theme in the interviews.

(Waters 1990, 23, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Choosing an Ancestry

An Example: Bill Kerrigan (see Waters 1990, 24)

Q: What is your answer to the census question?

A: I would have put Irish.

Q: Why would you have answered that?

A: Well, my dad’s name is Kerrigan and my mom’s name is O’Leary, and I do have some German in me, but if you figure it out, I am about 75 percent Irish, so I say I am Irish.

Q: You usually don’t say German when people ask?

A: No, no, I never say I am German. My dad just likes being Irish… I don’t know, I guess I just never think of myself as being German.

Q: So your dad’s father is the one who immigrated?

A: Yes. On this side it is Irish for generations. And then my grandmother’s name is Dubois, which is French, partly German, partly French, and then the rest of the family is all Irish. So it is only my maternal grandmother who messes up the line.

Choosing an Ancestry

Thus in the course of a few questions Bill labeled himself Irish, admitted to being part German but not identifying with it, and then as an afterthought added that he was also part French. His identification as Irish was quite strong, both culturally and socially, which explains his strong self-labeling. Further in the interview, however, he described a strong German influence as he was growing up … He reported that his mother was strongly committed to her German ancestry and would definitely have mentioned it along with her Irish ancestry on the census form. He said he never thought of himself as German, however.

(Waters 1990, 24–25, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Labels Given to Children

Parental Transmission?

Knowledge of one’s ethnic ancestry is the result of sifting, simplifying, and distorting the knowledge one has about it in interaction with the labels others attach to it. Among the most influential of these labels are those given to children by their parents.

(Waters 1990, 26, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Parental Transmission?

Adaptation of Table 1 in Waters (1990)

Note: Scroll to access the entire graphic

Interpretation

Average (rounded) share of children “correctly” labelled as a combination of parental ancestries in mixed households—by parental “origin.” Data drawn from the 1980 U.S. Census.

Parental Transmission?

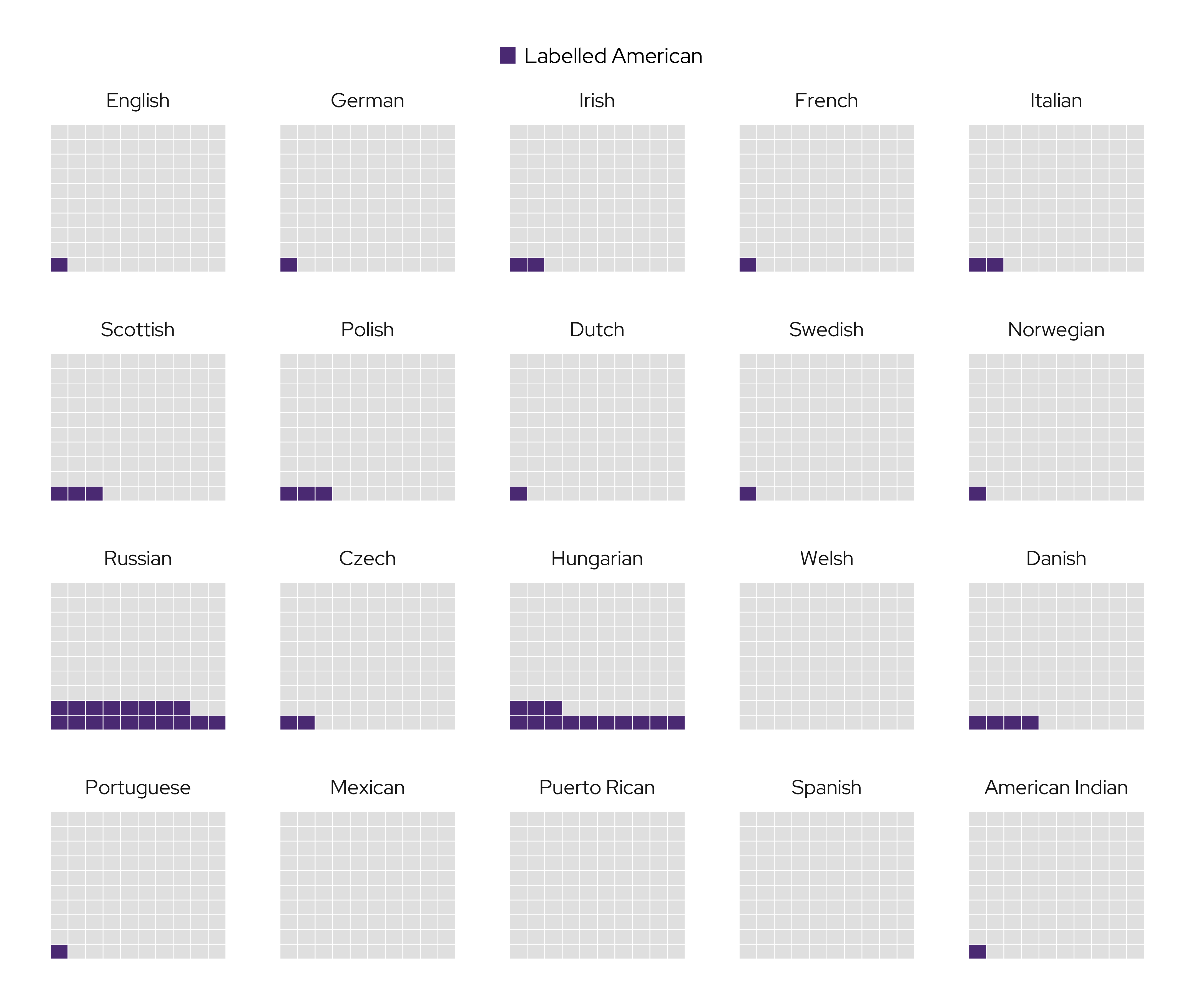

Adaptation of Table 2 in Waters (1990)

Note: Scroll to access the entire graphic

Interpretation

Average (rounded) share of children labelled “American” when parents share the same putative ancestry—by parental “origin.” Data drawn from the 1980 U.S. Census.

Parental Transmission?

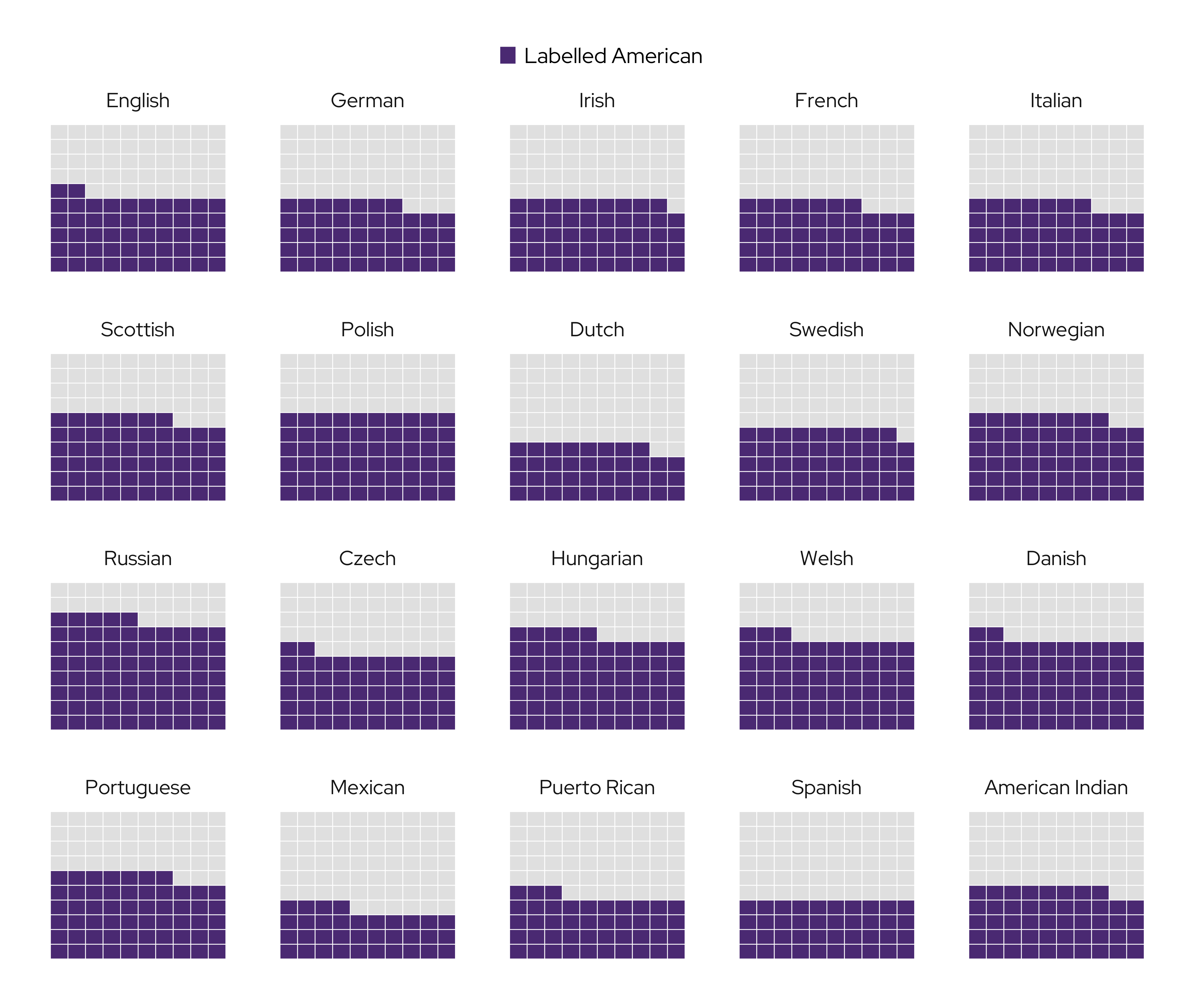

Another Adaptation of Table 2 in Waters (1990)

Note: Scroll to access the entire graphic

Interpretation

Average (rounded) share of children labelled “American” when respondent’s spouse claims American ancestry—by parental “origin.” Data drawn from the 1980 U.S. Census.

Simplification

Reducing Complexity

When sketching their self-portraits, do individuals of European “origin” stitch together all the ethnic labels that

are available to them?

Reducing Complexity

No.

Reducing Complexity

Adaptation of Table 4 in Waters (1990)

Reducing Complexity

Some ancestries, such as Italian, do appear to be more popular ones to simplify to, and some, such as Scottish, appear to be very unpopular in certain combinations. But how much of this is owing to the appeal of the ancestry label and how much to other factors, such as whether it is the mother or the father who has the particular ancestry?

(Waters 1990, 31, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Reducing Complexity

Parents’ Reported |

Simplified |

Chose Maternal |

Chose Parental |

|---|---|---|---|

English-German |

29.1 |

39.1 |

60.9 |

English-Irish |

35.9 |

36.8 |

63.1 |

English-Italian |

25.9 |

33.9 |

66 |

English-Scottish |

33.6 |

39.6 |

60.3 |

German-Irish |

21 |

33.4 |

66.6 |

German-Italian |

17 |

23.1 |

77 |

German-Scottish |

22.3 |

24.8 |

75.2 |

Irish-Scottish |

21.9 |

24.6 |

75.4 |

Italian-Scottish |

15.7 |

25 |

75 |

Reducing Complexity

| Ancestry A | Ancestry B | Parental Choice Ratios |

|---|---|---|

English |

German |

1.13 |

English |

Irish |

1.63 |

English |

Italian |

0.50 |

English |

Scottish |

6.18 |

German |

Irish |

1.00 |

German |

Italian |

0.45 |

German |

Scottish |

1.00 |

Irish |

Italian |

0.80 |

Irish |

Scottish |

4.48 |

Italian |

Scottish |

1,200.00 |

Temporal Variation

Consistency

Note: Scroll to access the entire table

| Ethnic Ancestry | Share Reporting the Same Origin in 1972 as in 1971 |

|---|---|

Puerto Rican |

96.5 |

Black |

94.2 |

Mexican |

88.3 |

Italian |

87.8 |

Cuban |

83.3 |

Polish |

79.2 |

Spanish |

78.9 |

German |

66.1 |

Other (Includes Multiple Ancestries) |

62.5 |

Russian |

62.3 |

French |

62.1 |

Irish |

57.1 |

English, Scottish, Welsh |

55.1 |

Don’t Know |

34.9 |

All Groups |

64.7 |

Age and Reported Ancestry

Adaptation of Table 12 in Waters (1990)

Group Discussion II

Interpreting Waters’ Results

In small groups, discuss what these results tell us about the assimilatory trajectories of European immigrants in America

(as dated as these results may be).

Lecture II: October 30th

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

Midterm Paper Deadline(s)

If you have yet to submit your midterm paper, it is due by —

- 8:00 PM on Friday, November 1st

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

To submit the paper, visit the following page on Moodle.

A Quick Reminder

Midterm Paper

Please submit the paper as a .docx or .doc file.

\(\LaTeX\) User?

Check outpandoc.

Two Invitations

Are any of you available on Wednesdays between

2:00 and 3:20 PM?

Two Invitations

Dr. Stephanie Ternullo will be joining us SOCI 229 on November 13th.

Two Invitations

Dr. Miloš Broćić will be joining SOCI 229 on December 11th.

Symbolic Ethnicity —

Herbert Gans

Gans’ Central Argument

In the late-1970s, there was no ethnic renewal or revival in America. Rather, we were witnessing the emergence of symbolic ethnicity

(Gans 1979).

Gans’ Central Argument

A Question

What do you think symbolic ethnicity means in concrete terms?Acculturation and Assimilation

In developing his argument, Gans (1979) invokes the spectre of

straight-line assimilation theory.

Acculturation and Assimilation

Straight-Line Assimilation (Stylized)

Acculturation and Assimilation

A Question

Can you name some of the scholars associated withstraight-line assimilation theory?

Acculturation and Assimilation

Gans (1979) identifies four critiques of the straight-line model—

Does not account for new migratory inflows.

Conflates all ethnic groups (e.g., those defined in ethnoreligious and ethnonational terms).

Does not account for ethnicity’s evolution or functional utility in meeting the exigencies of the present day.

Overestimates the prevalence of acculturation and structural assimilation—and conversely, underestimates the resilience and “revival” of ethnicity in the 1970s.

Acculturation and Assimilation

A Question

Does Gans (1979) agree with these criticisms?Acculturation and Assimilation

Not really.

Group Discussion III

Applicability of the Straight-Line Model

In groups of 2-3, discuss why Gans (1979) does not believe that these criticisms invalidate the straight-line model.

The Visibility of Ethnicity

Visibility’s Distortionary Effects

The recent upward social, and centrifugal geographic, mobility of ethnics, particularly Catholics, has finally enabled them to enter the middle and upper middle classes, where they have been noticed by the national mass media, which monitor primarily these strata. In the process they have also become more noticeable to other Americans. The newly visible may not participate more in ethnic groups and cultures than before, but their new visibility makes it appear as if ethnicity had been revived.

(Gans 1979, 5, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Visibility’s Distortionary Effects

Some pathways to visibility for European “ethnics” included—

Presence of Catholics in national politics.

Rise of Catholic “ethnic intellectuals” in the academy.

Emergence of Jewish (and other “ethnic”) comedians, writers and entertainers who embraced their origins.

Ethnicity in the Third Generation

A New Mode of Ethnicity

“[T]oday’s young ethnics are finding new ways of being ethnics, which I shall later label symbolic ethnicity”

(Gans 1979, 6, EMPHASIS ADDED).

A New Mode of Ethnicity

For the third generation, the secular ethnic cultures which the immigrants brought with them are now only an ancestral memory, or an exotic tradition to be savored once in a while in a museum or at an ethnic festival. The same is true of the ‘Americanization cultures’, the immigrant experience and adjustment in America … The old ethnic cultures serve no useful function for third generation ethnics who lack direct and indirect ties to the old country, and neither need nor have much knowledge about it. Similarly, the Americanization cultures have little meaning for people who grew up without the familial conflict over European and American ways that beset their fathers and mothers: the second generation which fought with and was often ashamed of immigrant parents.

(Gans 1979, 6, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A New Mode of Ethnicity

Some sociocultural patterns marking the European third-generation (of the 1970s) included—

Movement into non-ethnic primary groups (e.g., via exogamous relationships and intermarriage).

Movement out of ethnic cliques, homophilous social networks and professional or occupational spaces.

Residence in diverse neighbourhoods contra the ethnic clustering and spatial concentration of yore.

A New Mode of Ethnicity

Nevertheless, while ethnic ties continue to wane for the third generation, people of this generation continue to perceive themselves as ethnics, whether they define ethnicity in sacred or secular terms. Jews continue to remain Jews because the sacred and secular elements of their culture are strongly intertwined, but the Catholic ethnics also retain their secular or national identity, even though it is separate from their religion.

(Gans 1979, 7, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A New Mode of Ethnicity

My hypothesis is that in this generation, people are less and less interested in their ethnic cultures and organizations — both sacred and secular — and are instead more concerned with maintaining their ethnic identity, with the feeling of being Jewish, or Italian, or Polish, and with finding, ways of feeling and expressing that identity in suitable ways … Third generation ethnics can join an ethnic organization, or take part in formal or informal organizations composed largely of fellow-ethnics; but they can also find their identity by ‘affiliating’ with an abstract collectivity which does not exist as an interacting group. That collectivity, moreover, can be mythic or real, contemporary or historical.

(Gans 1979, 7, EMPHASIS ADDED)

A New Mode of Ethnicity

In other words, as the functions of ethnic cultures and groups diminish and identity becomes the primary way of being ethnic, ethnicity takes on an expressive rather than instrumental function in people’s lives, becoming more of a leisure-time activity and losing its relevance, say, to earning a living or regulating family life.

(Gans 1979, 9, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Symbolic Ethnicity

Its Expressions

Symbolic ethnicity can be expressed in a myriad of ways, but above all, I suspect, it is characterized by a nostalgic allegiance to the culture of the immigrant generation, or that of the old country; a love for and a pride in a tradition that can be felt without having to be incorporated in everyday behavior. The feelings can be directed at a generalized tradition, or at specific ones: a desire for the cohesive extended immigrant family, or for the obedience of children to parental authority, or the unambiguous orthodoxy of immigrant religion, or the old-fashioned despotic benevolence of the machine politician.

(Gans 1979, 9, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Its Expressions

As its name implies, symbolic ethnicity involves the transformation of “cultural patterns” into easily identifiable symbols or diacritics.

Its Expressions

A Question

What are some of the symbols Gans (1979) referred to?Group Discussion IV

Symbolic Ethnicity and the Straight-Line Model

In small groups, discuss whether Gans (1979) believes that symbolic ethnicity is compatible with straight-line assimilation theory.

The Twilight of Ethnicity — Richard Alba

American Catholics

Adaptation of Table 1 in Alba (1981)

Note

Data based on analysis of the General Social Survey (1973-1978).American Catholics

Adaptation of Table 2 in Alba (1981)

Note

Data based on analysis of the General Social Survey (1973-1978).American Catholics

Ethnicity, then, appears to be subsiding among the Catholic ethnic groups, although not disappearing entirely … My own suspicion is that this ethnic resurgence was more in the eyes of beholders than it was in events among the Catholic ethnics and, moreover, that the increased visibility of ethnicity was paradoxically a product of the same forces sapping ethnicity’s vitality. During the 1970s, ethnicity could be celebrated precisely because assimilation had proceeded far enough that ethnicity no longer seemed so threatening and divisive. Ethnicity was made more visible by the penetration of Catholic ethnics into positions of prominence in American life.

(Alba 1981, 96, EMPHASIS ADDED)

American Catholics

[T]he Catholic ethnic groups, so prominent a feature of the American social landscape for the better part of this century, seem destined as groups to recede into the background, at the same time that many Americans descended from these groups, still tinged by the ethnicity of their ancestors, move into the social heartland of America.

(Alba 1981, 97, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Enjoy the Weekend

References